Written by Mariano Falzone

Adventure games were highly popular in my home country of Argentina in the 90s and early 2000s, when I grew up. Actually paying for games, though, not so much. In our defense, video games were very expensive, the titles available were very scarce, and most parents, even if they could afford to buy one once in a while, never saw anything of value in them, or just didn’t know what all the fuss was about nor seemed to care. That’s why I and many other youngsters would spend our time scavenging through abandonware websites in Spanish. There were even many sites dedicated especially to adventure games, from both Spain and the Americas.

La Abadía del Crimen was a title that was always mentioned in those places. There was a cultish aura about it. I remember thinking that it looked interesting, but I was far more invested in LucasArts stuff, so I must’ve downloaded it, put it somewhere in my computer and forgotten about it. I mean, I could download Fate of Atlantis or Monkey Island in Spanish anyway. For all I knew, La Abadía del Crimen was just another translated American game. Only when I grew older did I learn that it was an 80s game from Spain and one that had never been translated into English, and why that made it unique.

Since then I’ve been reading and hearing about it every once in a while. I’ve also read Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, the novel on which the game is based on, and watched the Jean-Jacques Annaud film starring Sean Connery and a very young Christian Slater. But I still never played it. So I thought, “Hey, I’ll write to The Adventurers Guild and ask if they’d let me review it for the blog. If I’m gonna finally play it, let’s do it in style.” The answer was positive.

The period of 1983 to 1992 is referred to by many in Spain as the Golden Age of Spanish Software, with Spain becoming the second largest producer of video games, behind the United Kingdom. Companies such as Dinamic Software, Topo Soft, Made in Spain and Opera Soft enjoyed great success during this period, pushing the envelope in many genres, from platformers and shooters to, our main concern here, adventure games.

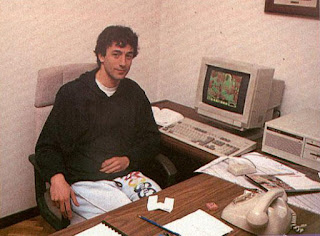

Paco Menéndez was a young programmer and college student of Telecommunications. As part of Made in Spain, he’d worked on the platformers Fred and, especially, on Sir Fred, its sequel, which is considered a cornerstone of Spanish video games. After the success of Sir Fred, Made in Spain wanted to expand as a company, making plans to publish what other studios were developing too. Menéndez didn’t like this corporate move at all, he just wanted to make his own thing, so he left to pursue his dream of developing his ultimate video game.

A childhood friend of Menéndez, Juan Delcán was an artist and college student of Architecture. He’d also been part of the Made in Spain bunch, though in interviews he’s humbly downplayed his involvement, saying that he just made a couple of covers and menu screens. Menéndez asked him to work with him doing the graphics on an adaptation of Eco’s The Name of the Rose. Delcán thought he was nuts, not only because of the ambition of the project, but also because Menéndez was convinced Umberto Eco would give them the rights. They wrote to him asking for them, and Eco declined, so they changed the name of the project to La Abadía del Crimen (The Abbey of Crime), which had supposedly been one of the working titles Eco was playing with before settling for the iconic final title. They also made a couple of little changes to the story, most notably changing the mysterious book involved in all the deaths in the novel (not going to spoil it in case anyone hasn’t read it yet and is planning to).

Delcán recalls, in the book Ocho Quilates: Una historia de la Edad de Oro del software español (1987-1992) (translated):

“Paco asked me to make a game for him. I was up to my ears in work, but it was hard to say no to Paco. He would get very excited, his eyes would get big and shiny, like in Japanese cartoons, and you couldn't say no to him. I accepted and he said he wanted to do something that would break with everything, that would be the most amazing thing in the world.”

Delcán used the opportunity to actually create a building from scratch using his knowledge of architecture, albeit in a digital world, studying many books on abbeys from all over Europe. He would draw the graphics and set pieces on graph paper, each little square representing a pixel, and Menéndez would then translate them into programming. Menéndez also implemented a sort of AI which was boundary-pushing for its time, making the monks in the abbey to behave a certain way and walk on their own through different rooms depending on many variables. His original code has attracted many opinions from his peers, some calling it a mess, others extremely elegant, but everyone agrees on the fact that they’d never seen something like it. He was doing everything he could to occupy the least disk space possible, and he kept the game under 200 kb.

They worked on the game for the most part of 1987, and Menéndez eventually self-published a very limited run of the game through the company Mister Chip, which was actually his father’s computer academy. Shortly after, Opera Soft, a major studio and publisher at the time, took notice, and the game was properly published through them for Amstrad CPC, ZX Spectrum, MSX and DOS in 1988. They also hired Paco Menéndez to work with them full time.

Dinamic Software had been making text adventures with graphics at least since 1984 (potential Missed Classics? Though their greatest claim to adventure game history would come in the 90s publishing the first three games from Pendulo Studios), but La Abadía del Crimen could arguably be considered the first graphic adventure originally made in Spanish. As it was like nothing they’d seen before within the frontiers of Spain, the game was a critical success and started gathering a slow but steady cult following, earning Menéndez an award for Best Programmer in a popular Spanish video game magazine.

But it wasn’t commercially successful. Nevertheless, the people at Opera Soft wanted him to make another game and asked him many times to do so, but he always refused. Those who knew Menéndez considered him both a genius and a difficult man to work with, not necessarily in the sense of being abusive or anything like that, but more due to the fact that he would work on whatever was his obsession at the time, relegating his employee duties and company projects if they didn’t grab his attention. He’d wanted to make just that game and move on.

La Abadía del Crimen would be the last game both Paco Menéndez and Juan Delcán would make. Delcán dropped out of studying architecture and moved to the United States, where he’s had a successful career in advertising. He now lives in New York, and his digital abbey remains, as far as I’m aware of, his only architectural work.

Paco Menéndez left Opera Soft in 1989. In an interview that same year, taken from the book Ocho Quilates previously mentioned, he explained his reasons:

"This is not what it used to be. Now it's all marketing. [...] It used to be an art, now it's all about money. [...] Anyway, I never planned to do this forever, I thought of it as a hobby, and I think the time has come to stop. [...] [I'm] going to continue my career in telecommunications and do research. I'm working on a computer with a completely new architecture and I'm also developing a new language for it. [...] If I decided to do something new it would have to be better than La Abadía del Crimen, and the effort that would take, I'm sure, would not be rewarded."

He spent the following decade doing just that, experimenting with hardware and software. Sadly, after several battles with depression, he ended his own life in 1999, at the age of 34.

The game has been enhanced and remade many times: a DOS version with 256 colors, a port to the Game Boy Advance, and, most recently, an expanded remake called The Abbey of Crime: Extensum, which can be played for free and in many languages, including English. On top of that, Amstrad CPC enthusiasts translated the original version into English. Finally, there’s a 2008 Spanish adventure game called The Abbey (also referred to as Murder in the Abbey), which is not actually a remake but it’s acknowledged by its creators as heavily influenced by and an hommage to the 1987 classic.

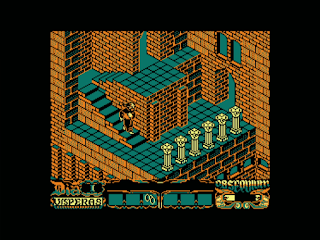

I’ll be playing the original Amstrad CPC version in Spanish myself. It’s not just the version its creators originally intended to create, but it’s also better-looking than the other 1988 versions.

Ok, so, after years of hearing about it, after the research, the praise, the legend, now it’s the time to actually play it and see how it holds up. I’ll admit that I’m going into this with a bit of a desire to really like it. I’ll try to leave my rose-tinted glasses in the drawer as much as I can, but I’m only human.

On with the game

It’s my first time playing an Amstrad CPC game, so it took me a little while to understand how to use the Retro Virtual Machine emulator, which, by the way, has the two heroes of our Spanish game right there on the main screen, along with someone that I guess is Conan the Barbarian. So far so good.

Then, the title screen sets up the mood perfectly (check it out at the beginning of this post). Shortly after, a lengthy introduction with each letter slowly being written on screen happens, to the tune of 8-bit Bach. It’s taken almost word for word from the first few pages of the novel, with an old Adso de Melk, who will be my young assistant during the game, writing from a monastery cell to finally set in ink the terrible events that happened long ago in an abbey that’s best left unnamed.

And so we start. Within the first few seconds, I come upon two things that will get some time getting used to. The first is the controls. I play as Guillermo de Occam (of Baskerville in the novel), with my faithful young assistant Adso de Melk following me around. The left and right arrows turn Guillermo around in his place, the up arrow makes him walk in the direction he’s facing. The down arrow, however, moves Adso in the direction Guillermo is facing, so you have a limited mobility control of him too. I notice that if you move Adso and he eventually faces a wall or an obstacle, he’ll turn to one side and just keep walking.

The second thing, and a controversial design choice that has everyone divided between thinking it’s either really interesting or awfully frustrating, is the camera system. You see, it’s an isometric game, but the camera angle changes when going from one room to the next.

Anyway, upon entering the abbey, we’re confronted by the Abbot, who hurriedly tells us something terrible has happened and that we should follow him. He walks quite fast, so keeping up the pace is kind of hard at first. And if he gets a few steps ahead too much, he comes back and tells you to hurry up. The dialogue shows up in a little bar, moving from right to left like a scrolling marquee sign. It’s a bit inconvenient, but an interesting design choice.

“Something terrible has happened!”

While we follow him, he tells us the gist of what’s going on and what the ground rules are. A monk has committed a crime, and we’re tasked to find him before someone named Bernardo Gui (an Inquisitor, though the game doesn’t tell me that) comes, so as to preserve the good name of the abbey. The rules are: assist to mass and meals, and not leave your cell at night. The abbot shows us our cell, and that’s that.

By now it’s clear that in this game the clock is constantly ticking. The bottom left part of the screen tells me which day it is and what time, expressed in canonical hours. From what I read before, I know I have seven days to solve the crime, and mass, meals and night come very fast. In fact, barely a minute after the Abbot leaves us, since I took such a long time following him to the cell while I got used to the controls, Adso tells me it’s time to go to church and just rushes off. The clunky controls, the cameras and the labyrinthine abbey make me lose him out of sight in seconds. And now something weird happens. A kind of cut scene shows me another monk wandering all around the abbey. He starts at the library entrance, then goes through many rooms to close some gates, then to many other rooms to finally stay in the kitchen.

Suddenly I’m back with Guillermo. I wander around trying to find either Adso or the church, with no luck. Night falls, bringing some nice blue and violet colour palette, and seconds later the Abbot comes rushing after me saying I haven’t obeyed his orders and that I shall leave the abbey forever.

And so I go again. Ok, no problem. I go through the little I’ve done till now, and I’m prepared to follow Adso when he tells me it’s church time! Except, not so much. He rushes off again and I lose him almost immediately. Luckily, after walking desperately around the abbey, I find the church. Adso, some monks and the Abbot are there. The Abbot tells me to go to my position. All right, which is…? I stand at various places: besides Adso, behind him, between the monks… but the Abbot loses patience, comes and tells me I disobeyed and to leave forever. Game over.

And so I go again. I play up to the point I lost the previous time and now I choose a spot to stand in the church and wait, two steps ahead of Adso. The weird cut scene comes on again, with the monk wandering the abbey, but now I discover that using the controls gets me away from watching the monk and back with Guillermo. After a little while, that same wandering monk comes to the church and takes his place. The Abbot says “Let us pray,” so I chose the correct spot. Success!

After praying there’s a cut and suddenly it’s night. The Abbot tells us all to go to our cells, and he’s pretty pushy, following Guillermo and Adso and constantly ordering us to enter our cell. If I take too long to enter our cell, the Abbot kicks us out. Which is what happens, of course. Game over.

And so I go again. I play up to that point and get into my cell on time now. Why haven’t I been saving the game? I got too carried away wishing to make some progress and completely forgot. The one-page manual said I could save by using Ctrl + F1 to 9, having 9 save slots, and load with Alt + F1 to 9. It’s on!

Once in our cell, Adso asks if we should go to sleep. You can choose whether to turn in for the night or wander through the abbey. Let’s explore, why not! I don’t really know what I’ll be looking for, but at least I’ll get a lay of the land and maybe find something.

I find out that all doors are locked at night, so some shortcuts are off-limits. After a bit of night-roving, the Abbot, who does a constant night watch, finds us and tells us to leave forever. Game over. But this time I load just before going to bed, so no starting again! Progress!

So I let this night go and go to sleep. At the start of Day 2 we’re summoned to church. Once the monks are there, the Abbot informs us that brother Venancio has been murdered. After that, the monks are free to leave, except for Adso and me. The Abbot has one more message for us: the library is off-limits to everyone, only Malaquias can enter. Got it.

Time to find the library then. After a few rooms, a monk intercepts us, wanting to talk to us. His name is Severino, he’s in charge of the hospital, and he seems scared. He says weird things are happening in the abbey and the monks are not allowed to decide for themselves what they should learn.

By the way, I forgot to mention there’s an inventory too. Guillermo can carry six items and Adso can carry two, according to the manual. Pressing the spacebar makes you pick up or leave items, and only Guillermo can do that. When I started I only had a pair of glasses, but at the start of Day 2 they’re gone! The game didn’t tell me anything about it, but I read somewhere else that I’m supposed to understand someone stole them during the night.

Another thing I haven’t mentioned is the Obsequium level bar. Obsequium is Latin for subservience or obedience (per Wikipedia), and if the level bar depletes, the Abbot will kick us out. You’re supposed to keep the level above zero by following the rules and not disobeying, although I’m not sure what kind of little offenses are taken into consideration yet, because the bigger ones, as we’ve seen already, grant you an automatic expulsion.

So I keep exploring, trying to get to the church. There are some monks coming and going, which, coupled with the gorgeous design, makes the abbey come truly alive. At a certain point, Adso announces that it’s time to go to the refectory for our meal and rushes off. I almost lose him again too, but I arrive at the refectory on time. Adso and some monks are at the table, with the Abbot at the head, who now tells me to occupy my place. I go near the table, and he says it again. I move to every place near the table, and he keeps telling me to occupy my place.

Of course, he loses patience and kicks us out. Game over. I load back and somehow manage to occupy my given place in one of the first tries. We eat, and the Abbot and monks go their separate ways. After a little more exploring, I finally find the entrance to the library. Malaquias is there and he tells us that we cannot go up to the Library. There’s a key on a table here, the quintessential item in adventure gaming. (Future-Me note: after I played this session, while researching images, I came upon a tip from a 1987 magazine which said how to get the key, so I got an accidental spoiler. I’ll try it in my next session.)

Malaquias is halfway through a phrase about how brother Berengario can show us something when a constant alarm starts sounding off (the same sound used when we need to go to church or to the refectory) and he tells us we should abandon the building immediately, with he and Adso rushing off. I follow Malaquias, who says he’ll give a heads up to the Abbot. But then I lose him. I wander around and find on a table a scroll and a book, and pick them up. And just when I’m about to climb down some stairs, I get the message “You are dead, friar Guillermo, you have fallen into the trap”, with Guillermo lifting up into the air as if he’s ascending to Heaven or something. I have no idea whatsoever what just happened. So, of course, game over.

So I load back. This time, at the entrance of the Library, Malaquias finishes his sentence and tells us Berengario can show us the Scriptorium. Berengario promptly shows up, saying that the best copyists in the West work here, and we follow him for a couple of rooms until we reach the Scriptorium. Once we get there, he informs us that Venancio used to work there. This is the room where I found the scroll and the book previously, when no one was here. I pick up the scroll now and Berengario warns me: “Leave Venancio’s scroll or I will tell the Abbot.” Berengario then leaves, and I’m not sure whether to steal these items now or leave them for the night. After some more reconnaissance of the building, I come back and pick them up anyway. Shortly after, some rooms later, the “You died and fell into the trap” message suddenly comes up again. I gather that picking up the book and/or the scroll is what this trap’s about and what leads to my demise? I guess the book is the death trap, if the source material is being followed here.

So I load back to when Berengario shows us the Scriptorium and don’t pick up any items this time. A little later, it’s time to go and pray at church again. The cut scene of the monk, who I think is Malaquias now, doing his round of the abbey and closing the gates comes up, ending with the monk in the kitchen, a place I haven’t been to yet. Cut back to the church, and night falls after praying, so it’s time to hurry and go to the cell. Once there, I decide not to go to sleep and explore instead.

The Abbot roams the Abbey at night, that man never sleeps, and it’s quite hard not to get noticed and caught by him. In my round now, it happens quite a few times, so I’m using 8 of the 9 save slots to do everything I can.

And then both the game and I mess up real bad. I use up my 9th save slot, wander a little bit more, get caught again, and when I load back there… all I did since I saved on that slot is played like a movie before me. I can’t control the characters at all, it just plays exactly as I played it. This must be a bug, it’s just too weird. So, in all my wisdom, I reset the emulator and the game. But when I load any of the 9 saved slots, they’re completely different to mine. Every single one. Some of them are on days I haven’t even gotten to. The silver lining is that now I discover that the Retro Virtual Machine has a much more reliable save system, one that I could’ve used since the beginning. Oh well.

Session time: 1h 40m

Total time: 1h 40m

Perfect moment to wrap this post. For a second I thought about using one of those saved slots that come with the game, from day 3 for example, but nah. I’ll replay it from the beginning next time.

I can’t deny it’s been a little bit frustrating, but I’ve also been enjoying it a lot, in a no-way-I’m-gonna-let-this-game-beat-me kind of way. The graphics and the design of the abbey alone, exploring just to get lost, has been enough of a joy during this session. Or maybe I couldn’t put down my rose-tinted glasses after all. We’ll find out next time, when hopefully I beat it and run it through the grinder of the PISSED system, and, as this is an introductory post, feel free to guess in the comments what the Final Rating will be.

Thanks again to Joe and Ilmari for the opportunity to review this Missed Classic, and also to the resident Spanish Reviewer Deimar for nudging me towards the books Obsequium: Un relato cultural, tecnológico y emocional de La Abadía del Crimen and Ocho Quilates, which have been invaluable resources.

Until next time!

Note Regarding Spoilers and Companion Assist Points: There's a set of rules regarding spoilers and companion assist points. Please read it here before making any comments that could be considered a spoiler in any way. The short of it is that no CAPs will be given for hints or spoilers given in advance of me requiring one. As this is an introduction post, it's an opportunity for readers to bet 10 CAPs (only if they already have them) that I won't be able to solve a puzzle without putting in an official Request for Assistance: remember to use ROT13 for betting. If you get it right, you will be rewarded with 20 CAPs in return. It's also your chance to predict what the final rating will be for the game. Voters can predict whatever score they want, regardless of whether someone else has already chosen it. All correct (or nearest) votes will go into a draw.

I've always loved the graphics and atmosphere in this game (I played the ZX Spectrum version at the time), but never went far in it. IMO, it's hurt by the lack of a feature that a very similar game, The Great Escape (by Ocean) had: if you let go of the controls for a bit, your character does the camp routine automatically (attending roll call, going to meals, sleeping in your bed, etc.). Having to do them manually every day is frustrating, especially with these controls.

ReplyDeleteYeah, I can't help but agree with you. On paper, the design choice makes sense, you have more interactivity and tasks to do. In practice, it's kind of a drag. I saw The Great Escape mentioned a few times when researching. Although I haven't seen any confirmation, it is very probable that Menéndez was influenced by it, as he seems to have been very fond of Ocean's games, according to friends and colleagues.

Delete“You are dead, friar Guillermo, you have fallen into the trap”

ReplyDeleteDoes the dialog bar here say "Estais muerto"? As in, the familiar plural?

This comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteI think they are using "plural mayestático" (majestic plural or royal we), a very formal way to address to a single person using a plural pronoun, which usually was used for addressing to a monarch or another high-office person. I suppose this would be the Spanish equivalent of saying "Thou are dead".

DeleteI didn't know languages other than English did that. Neat!

DeleteI think Agrivar is 100% right!

Delete"Thou" is actually informal in English. "You" is the formal version.

DeleteModern speakers get confused because, being obsolete, "Thou" sounds old-fashioned, and being old-fashioned makes things "feel" more formal. There are references to "Thou-ing" (ie, addressing someone of high status with informal usage) someone being a grave insult. (If you know your romance languages, you can kinda see a vague familial resemblance between the english "Thou" and the French/Spanish "Tu", likewise a more distant resemblance between "You" and "Vous").

The King James Bible uses "Thou" for God, which probably also enforces the modern notion of formality, but in context, it's intended to express a parent/child relationship.

I've heard some people say that "Thou" was basically killed in English by Plain People groups (Amish, Mennonites, etc) - they made a point of using it all the time to stress equality, but because they were a social outgroup, "normal" people didn't want to talk like them.

Another reason for the death of "thou" I've heard is it being increasingly perceived as impolite, and it was better to err on the side of politeness.

DeleteI'm guessing "thou" is also a cognate with the German & Swedish "du", like the archaic "wherefore" probably is with the Swedish "varför".

Looks like a very interesting (although potentially quite frustrating!) game!

ReplyDeleteTo my shame, I've never read the book or even watched the movie version, perhaps I'll do that to help me follow along.

The book is great! I have my reservations about the film, especially with regards to the ending, but it's a fine film in its own right nonetheless.

DeleteWelcome to the guild, Mariano! Great post.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Joe!

DeleteWelcome, Mariano! If you're interested in more adventure games from the "Spanish Golden Age of Videogames", maybe you should take a look to the text adventures developed by the company "Aventuras AD", like the trilogy of Cozumel and "La Aventura Original". Keep in mind, though, that these adventures are quite hard, not only by many dead-man walking situations, but also because that had some minor random elements: in "La Aventura Original" there was an enemy who appeared randomly, and if you had the misfortune of encounter him three times, he killed you. I also suspect that my inability to finis the first game of the Cozumel trilogy even while following a guide was by some random factor, because I kept dying from high fever for no reason and nothing from the guide mentioned the possibility of dying from fever nor mentioned any possible cure.

ReplyDeleteI hadn't heard about Aventuras AD before researching for this post, it sure sounds like their output was really interesting. Thanks for the info and recommendations, I'll check them out!

DeleteIf you want to do some research about Spanish text adventures, keep in mind that the name given in Spain for text adventures was "aventuras conversacionales".

Deletehttps://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aventura_conversacional

Great, thanks for the tip!

DeleteEs un juego que solo puede ser entendido en el contexto de la época, y la mejor manera de jugarlo es con una guía o solución , es complejo y requiere de precisión y timing para completarlo , pero solo si lo conociste en aquella época podrás experimentar y entender al máximo hasta donde llega La Abadía del Crimen, es de los pocos juegos que no pueden ser extrapolados a nuevos jugadores al 100%

ReplyDeleteVoy a intentar jugarlo sin guia lo más posible, pero creo que tienes razón y no voy a durar mucho sin buscar más pistas (que ya tuve algunas). Gracias por comentar!

DeleteDe nada, en nuestro país es un juego de culto, hay multitud de material de revistas preservadas con la solución que te pueden ayudar, o usar una guía mucho más moderna. La mejor versión es la de CPC 128k y la de DOS en CGA.

DeleteHey El Conde de Montecristo, Anonymous from Spain here. Just a kind suggestion: since this blog is written in English, perhaps you should try to write your comments in English too so everyone around the world can understand you without having to paste your text in Google Translate. No todo el mundo sabe español, compañero. ; )

Delete"The period of 1983 to 1992 is referred to by many in Spain as the Golden Age of Spanish Software, with Spain becoming the second largest producer of video games, behind the United Kingdom."

ReplyDeleteI'm from Spain and I must correct that statement. That can only be true if we count video games released in Spain for the Amstrad CPC and ZX Spectrum. If we count every single platform including MSX, Commodore 64, NES and even arcades, there are many more American and Japanese games (and even French).

It seems to be a quote taken directly from the English translation of the Spanish Wikipedia page about the period ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_age_of_Spanish_software ), but the original Spanish version only mentions "one of the biggest" and adds "for 8 bit computers, especially for the ZX Spectrum".

I meant that Spain was the second largest in Europe, but I completely forgot to clarify that part. The US and Japan were always ahead of everyone in production, as you say. Thanks for the heads up!

Deletealways hated this game, as most spanish games are really weird for latin american spanish. Also, it reminds me a lot to the Heimdall games, not really adventures, but had some puzzles thrown in.

ReplyDeleteHadn't heard of the Heimdall games, but seeing their isometric medieval vibes, it makes sense!

DeleteSpaniard here. I was never too interested in Spanish games. I had 3 or 4 for the Amstrad CPC as a child and the only good one was the text adventure Megacorp (quite good sci-fi adventure with not too easy or too difficult puzzles, I recommend it). However, I wonder what you were trying to say with "weird for Latin American Spanish (speakers)". Do you mean the language variant, like using the verb "coger" (which means "fuck" colloquially in some Latin American countries?)? In any case, Spanish action games from the 80s looked quite good, but were extremely difficult (due to a lack of proper testing). I find our golden age quite over rated.

Deleteyes both. Spoken spanish from Spain is so weird that is impossible to be immersed. Can't see any spanish movie, no important how dramatic or serious, without laughing. The way they talk is way over the top.

DeleteAlso, the low quality of their games, lack of testing, etc. Try Igor for example, or Hollywood Monsters, or Drascula .. most of the puzzles are so weird. It's like they were copying the LucasArts games but without the charm and logic.

This game always interested me, but seeing it in action makes me glad I'm not the one playing it. Great read though.

ReplyDeleteI'll guess 25 for the score.

Glad you liked it!!

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteGraphics great, timed games a big worry, but it does seem ground breaking with moving people. Let's try 33 for the score.

ReplyDeleteHaving no idea about the book or the film, may I ask what time period it is set in? It seems like it is set in the medieval times but since it is a monastery it could also be 19th century or so just very isolated. I'm too afraid to Google it for fear of spoilers.

Oh and can we make friendly bets about who gets killed next? My money is on Severino, he seems to be asking too many valid questions!

It's set in 1327.

DeletePoor Severino, let's hope he makes it!

DeleteThe zx spectrum 128k version in UK was translated to english

ReplyDelete"Adventure games were highly popular in my home country of Argentina in the 90s and early 2000s, when I grew up. Actually paying for games, though, not so much".

ReplyDeleteThat brings so much memories. In my case, from the late 80's to the mid 90's I payed for games, but they were pirated games that were sold in little shops (in gallerias or malls). I believe up to 1995 it was almost immposible to find legit games, so don`t feel bad for needing to use abandonware sites (I discover them from 2000 on, i download tons of games from House of the Underdogs and play none of them.....).

Regarding La Abadía del Crimen, I read a lot of stuff of this game from the spanish magazine Micromania (an awesome, but incredibly big sized magazine) that reach the kiosks in Argentina seven or eight months after their publication in Spain.

I have a very soft spot for isometric games, and i think that the graphics looks awesome even today. I tried it a little some years ago but, boy, it was very frustrating to play, and i abandoned it very quickly (same thing happened to me with The Great Escape for the C-64).

Anyways Mariano, you did great on your first post, keep on the good work!!!! I specially liked all the background information your provide us, it reminds me of Joe Pranovich's posts.

I'm going to bet a 35 score for this one, i think the graphics and the story will compensate for the other bad aspects of the game

Looking forward to know how this will continue....

Thanks, Leo! I used to frequent the Underdogs site too, and I vaguely remember the Micromania magazine. I also used to buy pirated copies of games when I was a teenager, but mainly through a catalogue and a guy you had to call to deliver to you whatever titles you asked for. Weird times!

DeleteAm a bit late to do this, but as there is no second post yet, I'm going to guess 40. I played a bit of an English remake over a decade ago, and soon gave up. I might try to play along, giving it another chance.

ReplyDeleteNot late at all! It is a frustratingly difficult game, but I believe the remakes make it a much more pleasant experience, though I haven't played them myself. Second post is coming soon!

Delete