Written by Joe Pranevich

|

As we approached our 100th Missed Classic, we had a tremendous challenge. What game could possibly be interesting enough or “classic” enough to warrant the 100th spot? With so many games played, most of the obvious candidates were completed long ago. We’ve played the first adventures, early games from later designers, and best sellers. Our 100th game needed to be more than that. We wanted to find a game that didn’t just look back on the history of our genre, but would look forward to the next iteration.

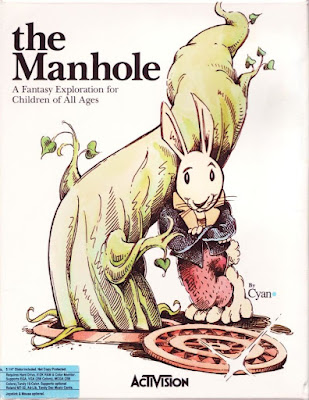

In the near future, we will be looking at Myst (1993). At arguably more than 7 million copies sold, Myst is certainly the best-selling adventure game of all time. Games like Myst and The 7th Guest (also 1993) will lead to major changes in adventure gaming, and some will claim the death of the genre. We’ll get to those topics in time, but before we can look ahead to Myst, we need to look back at its less well-known but hardly less amazing predecessor: The Manhole. As much an interactive experience as an adventure game, The Manhole stripped our genre to its most minimalist components. It doesn’t put icons or verbs between the player and the action, nor does it have a plot or real puzzles. The Manhole opens into an immersive world of whimsy and heart. The story of The Manhole is the story of two brothers, Rand and Robyn Miller, and an exciting new programming system for the Macintosh called “HyperCard”. They changed adventure gaming forever.

|

Robyn and Rand Miller (Undated Photo) |

Our story begins with the nomadic Miller family; Rand and Robyn’s father was a preacher who moved his family frequently according to his calling. Rand, the eldest brother, was born in 1958. He would soon be greeted by three more siblings. Robyn, the third son, was born in 1966.

It was in Albuquerque, New Mexico where Rand was introduced to his first computer-- and his first computer game-- 1969’s Lunar Lander. Rand quickly realized that computers were his calling. He learned programming and dabbled in creating games of his own. As a high school student, he wrote the game Swarms for the PDP-10. This effort won him second place in the 1976 National Student Computer Fair. In this game, deadly “African Bees” attack the United States. Although I can only glean a bit from reading the source, it appears that you can “solve” this problem by nuking areas of the country to prevent the spread of the swarm. It’s a dark picture, perhaps made less dark because Rand lived in Honolulu at the time and would have been safe from the mainland nuclear fallout. Swarms was ported to the Apple II and other systems; it’s unclear to me whether Rand received any compensation from these releases. Rand continued his computer studies through college and settled down to work for the Citizens National Bank of Henderson, in east Texas.

|

A map of the United States from a version of Swarms. |

Robyn could not have been more different than his brother. Born in 1966, seven years younger than his older sibling, Robyn took to music and art as his passion. He learned to paint and as a youth dreamed of becoming a Disney animator. Later, he transitioned to music and took to both piano and guitar. By this point, Miller's parents lived outside of Seattle, Washington and Robyn enrolled in the University of Washington to study Cultural Anthropology. Perhaps due to his family’s frequent moves, Robyn did not qualify for in-state tuition and took a year off to establish residency. (In the United States, state universities are significantly less expensive for residents of those states. In 2020, for example, the University of Washington where Robyn attended costs residents less than a third of what out-of-state students pay.) During this gap year, Robyn lived with his parents and worked on “awful novels”. As an aspiring artist, musician, and writer, Robyn’s boundless creativity was more than an equal to his brother’s technical prowess.

Enter, HyperCard. The Miller family had been early adopters of the Macintosh: Rand owned one at his home in Texas, while Robyn’s parents also had one in their home. Released in 1987 by Apple, HyperCard was the first visual development environment, and perhaps the most user-friendly programming system of all time. In an era when programming even graphical applications involved poring over hundreds of lines of inscrutable code in a text editor, HyperCard allowed programmers to assemble graphical views and connect “cards” in a “stack” in a way that resembles the development of hypertext, 6 years later. It made programming easy and accessible. It encouraged a new style of interaction. I still have amazing memories of creating little games and applications on my own early Macs. More importantly, HyperCard’s visual programming tools could bridge the skillsets of the two Miller brothers.

|

The “Home Card” was our starting point. |

Rand had exactly that thought. After working on some small stacks on his own, he lamented that there were few (if any) Macintosh games for his young children. He conceived of a video storybook that he could create with HyperCard, but he didn’t have the talent for it. He reached out to his brother and they began crafting together-- long distance-- the game that would become The Manhole. One of Robyn’s first sketches for the book was of a lonely manhole and nearby fire hydrant. Although initially envisioned as a storybook with basic interactions on each page, Robyn realized that he didn’t want to interact with the hydrant and then turn the page, he wanted the interactions to be the way the game was navigated. The game quickly became non-linear, almost a stream of consciousness. If a reader/player wanted to interact with the manhole, they could. If they wanted to check out the hydrant, they could. And from there, Robyn and Rand created more and more scenes, connecting them through clickable points on the HyperCard stack. The game wasn’t all static: HyperCard let them add simple animations and sounds as well.

The game took nearly a year to develop as a part time project for the two brothers. Rand continued with his bank job, while Robyn had other activities as a young student. In 1988, they traveled to San Francisco for the inaugural “Hyper Expo” trade show. On the floor were many aspiring companies excited by the possibilities of the new medium. They brought an early version of The Manhole (running on five floppies) and sold it out of their booth using homemade packaging. This early version of the game was credited on the box solely to Robyn Miller. Representatives from Activision fell in love with the game and soon rewarded the pair with a distribution deal and $20,000 (roughly $48K in today’s terms); it was not a significant sum of money for a year’s labor, but it put the game and the two brothers on the map. They founded “Cyan” (later “Cyan Worlds”) out of their parents basement. The brothers completed final tweaks (expanding the game by another floppy’s worth of content) and The Manhole was released. The game was immediately a critical hit, earning acclaim by MacWorld and the Software Publishers Association. The following year, Activision and Cyan re-released The Manhole as the first CD-ROM adventure game. The re-release included a full background soundtrack by Russell Lieblich. In 1990, the game was colorized and released for MS-DOS. A “Masterpiece Edition” with additional content was released in 1995.

Over the next several years, Rand and Robyn continued as game designers for Activision, exclusively making HyperCard-style adventures for children. They released Cosmic Osmo (1989) and Spelunx (1991), but their attempts to make a more mature adventure game for adults was stymied by Activision who encouraged (or demanded) that the Miller brothers stay in their lane. It wasn’t until the deal was in shambles that they could finally release a more mature product, the little-known title Myst. That will be a story for another day.

|

You might have heard of this one. |

Before we play the game, I have an admission: I will not be playing this game unspoiled. I first encountered The Manhole shortly after its release, in 1989 or so. I was eleven and would spend a week or two each summer with my aunt, a real Macintosh fan. She had just purchased a Mac IIcx for her family as well as games for her kids (and the original Leisure Suit Larry for herself). While I admit that I snuck more than a bit of time on LSL that year (my vocabulary was vastly expanded), I also spent a good deal of time delving into The Manhole. I don’t remember the exploring as much as I recall what it felt like to have a completely immersive adventure. I loved books and the simple, pen-like drawings appealed to me. I’m sure that I became bored of the game before too long, but The Manhole opened my eyes.

With my aunt’s help and a hand-me-down Macintosh Portable, I obtained my own copy of HyperCard and experimented to build my own simple games. I had already tried my hand at Commodore 64 BASIC and I knew the rudiments of programming, but HyperCard was much different. The programming language was easy to do simple things with and supported crazy things that no programmer would do. I recall being amused that they hard-coded “one”, “two”, etc. as written out constants in the language. You could write “one + two” and get the correct result. I don’t think I made any games, but I distinctly remember coding a scientific calculator and a clock. Both of them were horrendously slow on the 68000 processor in the Portable (my aunt’s IIxc was a 68030). (To put it in Intel terms, the Portable was running an old 8088 while the IIcx was a 386.) To make matters worse, manipulating the cards triggered a disk write on every interaction, even entering a number on the calculator! I’m sure in retrospect that there was a way around this, but my preteen self never found it.

I’m sorry, but I will be biased about this game. It may be just a toy, but far more than my Commodore 64 ever did, it inspired me. It made me feel immersed in a world for the first time as a player, and it inspired me to want to build my own. That is high praise. I’ll do my best to not let the biases shine through.

|

This scene screams out possibilities. |

Playing the Game

Welcome to the world in and around The Manhole. Remember this is not a race, and you don't win or lose. The idea behind The Manhole is exploration. Take your time, look around, click on everything, and enjoy the journey. Every time you play, you'll probably find something new.

How do we talk about an adventure game that isn’t an adventure game? With seemingly no puzzles or plot, our regular tools to talk about a game fail us. The Manhole is an adventure into Wonderland, a collection of interesting characters and scenes. I will approach it by narrating three short trips into its interior, one for each of the directions you can take when confronted with the closed manhole cover.

For clarity, I will be playing the original Macintosh floppy disc version. I am doing so in a PPC Mac emulator as I am unable to get a 68k Mac emulator working with HyperCard; as a result, some of the graphics and sound pass by more quickly than intended and it is difficult to get perfect screenshots. Thanks to the Digital Antiquarian, I have listened to much of the CD-ROM soundtrack and will include that in my review. I have also played the MS-DOS version and will include some notes about it at the end.

|

Jack never had two options. |

We start at the titular manhole. A fire hydrant drips nearby. The leaves that poke up under the cover suggest that something isn’t quite right. The stark white background suggests an illustration on the page rather than a “real” location; we’re not encouraged to ponder too much on the urban trappings in an unusual setting. Opening the manhole (by clicking on it) causes a beanstalk to emerge and rise into the sky. But unlike with Jack, we’re not just limited to climbing up: the beanstalk also descends into the depths below. We also have the option to ignore the beanstalk altogether and investigate the fire hydrant.

That gives us (at least) three options to explore. Let’s explore them one-by-one.

|

The beanstalk leads to… a hole in the sky? |

Up The Beanstalk

The most natural thing seems to be to climb up the beanstalk. When I presented this to my son (now eight), that’s what he picked. We climb the beanstalk, each click taking us higher and higher on the stalk. Unlike in Kings Quest I (1984), the beanstalk isn’t a frustrating challenge inches from certain death. Before long, we find ourselves at a hole in the sky, a manhole-shaped entrance that takes us out of the white expanse and into another terrain entirely.

We emerge into a moonlit forest as a dragon flies in the distance towards a dark tower. It’s a more traditional fantasy landscape, but completely divorced from the world below. As we explore, we discover a door at the base of the tower. Rather than going inside, we also spy ancient ruins just behind. Which way to go? I select the ruins.

|

A puzzle! Sort of! |

The ruins themselves appear vaguely Greek with tall pillars and water pouring out from a head into a deep pool. We can see a door underwater, but no obvious way to get there. This turns out to be one of only a few “puzzles” that I found in the game. While we cannot progress directly into the pool, we can click to explore around the columns. Behind one of them is a note (that we can edit; it leaves a file on disk for other players of the same copy to find), but another column triggers the pool to drain. Once drained, we can descend into the labyrinth below.

The torch-lit labyrinth isn’t large, but there are at least four exits from a central hub. One leads back the way I came, but I select the left-most tunnel to discover a door labeled “Mr. Dragon”. I press a doorbell nearby and am let in to discover a dragon lounging on a chair wearing sunglasses. He’s not at all what we expected!

|

“Hey baby, welcome to my cool pad. Make yourself comfortable. Have a biscuit, baby.” |

If you accept his offer of a biscuit, the dragon offers to warm it up-- only to roast it to ashes before our eyes. I wondered for a while if this game wasn’t British given the use of “biscuit” as what we might call a “cookie”, but it’s all in black-and-white. Perhaps he was just a British dragon? Or maybe he is handing out savory biscuits? Exploring his room further, we discover a path back to the outside of the tower that we saw earlier. We also can locate a remote control for his TV. By changing the channel and walking into the TV, we can warp to any of the denizens of The Manhole that we choose to visit, but the trip turns out to be one-way. My trip to visit a starfish brings me to a very different area and I elect to start over again and explore a different path.

|

| The animation goes by a bit fast to catch. |

Under the Beanstalk

Let’s start over! Instead of climbing the beanstalk like any sane person, I notice that it begins well under the manhole. Therefore, I get an option that Jack never did: climb down. I descend to somehow find myself on an island in a sea underneath the world. A turtle greets us… in French! A helpful fish translates. It’s such a cute moment (and will be revisited a few times in the next several scenes), but somewhat ruined by the overly fast speed of the game on a PPC Mac. That’s okay; I know what was supposed to happen.

The theme of this attempt is “go down” so I dive underneath the waves to see what is below. Thankfully, breathing is no issue and I quickly discover a shipwreck. I recognize it immediately as where I ended up after playing with the dragon’s TV, so I didn’t lose that much by starting over after all. In the crow’s nest of the ship is a family of seahorses, but I keep going down. Entering the ship’s hold, I discover a sleeping walrus, the captain’s quarters, and… an elevator. Ignoring the absurdity of an elevator on a sunken wooden shipwreck, I search the cabin where I discover a phone, a piano (that you can play, apparently), another notepad, and other odds and ends.

|

The sunken remains of an 18th century naval vessel. And starfish. |

As cute as the ship is-- and it’s very cute-- I eventually decide to leave the painting of “Sir Walter Wall Rus III” (either the walrus or his ancestor) behind and enter the elevator. When we do, the Walrus climbs in to join us. While six floors are listed, we can only travel from the 1st (where we are now) to the 6th. We ascend and I have no idea how this could work, but that really is the point. We find ourselves in a wooden shack that at first seems like it could be part of the ship, but we emerge to discover that we’re on an island. To make matters stranger, the island is in a room (with a well-labeled “Exit” sign) and an elephant dressed in traditional Indian clothing offers to let me ride on his (or her?) boat. How can you even explain this world without seeming crazy?

|

I’ve had the strangest day. |

When confronted by a friendly elephant with a boat, the only thing I can do is take him (or her?) up on the offer. Sailing out of the room, we find ourselves in a maze of canals in a big building. One room contains a floating chessboard. Taking a different set of passages, we arrive (somehow) inside of a gigantic teacup. There’s a straw in the cup, so it must not be hot tea. Who drinks out of a teacup with a straw, anyway? There’s an even more gigantic rabbit nearby. He spots the “tiny boat in my teacup” and then goes straight back to sleep.

Unless there is a puzzle here, I can find no way out of the cup in this direction. We cannot, for example, climb the straw. I follow the path out of the teacup and into a much wider room where we can disembark onto either bank. For some reason, the setup reminds me of the “It’s A Small World” ride in Disney World, but I cannot explain exactly why. Exploring a tunnel offshoot, I quickly find my way back to the four-way intersection near where I met the dragon last time. It’s an amazing adventure, but I think it’s time to move on.

|

Why climb a beanstalk when you can explore a hydrant? |

The Fire Hydrant

Starting over from the beginning, the third path that I can take is a bit more subtle. After opening the manhole-- and only then-- we can click over to investigate the fire hydrant. It has a sign on it that says “Touch Me”. In the game’s most overt reference to Alice yet, doing so shrinks us down and we stand at a door at the base of the hydrant. Peeking in a nearby mailbox, we find a letter from the Walrus to the Rabbit, complaining of all of the children wandering around and causing a ruckus. (Ha! We also learn that he is the son of the Walrus in the painting.) Inside is Rabbit’s much more modest house, just two rooms. He’s watching TV and drinking soda on a chair. Our milk straw is the same one that we saw earlier while exploring on the boat. This really is the same rabbit… Imagine, if we shrunk down small enough to see him, and we were previously small enough to boat inside his teacup… how small must we have been!? This is an excellent little brain teaser for children and I love it.

Other great details in his house include a painting of hats that changes every time you click on it, a collection of books both on a shelf and in his dresser, and much more. Just about everything in his house can be interacted with: we can turn off and on the light, adjust the picture on his TV, open and close the windows, and more. A fantasy book in the dresser transports us back to the dragon, if we want to go there.

|

When logic and proportion have fallen sloppy dead. |

Curiously, the books on Rabbit’s shelf clearly show the inspirations for the game. He has Alice in Wonderland; The Wind in the Willows; The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe; Winnie the Pooh; and Metaphors of Intercultural Philosophy. The first four of those books are classics of children’s literature, while the last is an invention of the Miller brothers. The caption tells us that the book “really isn’t about anything”. While I am fond of Wonderland and Pooh (and my opinions of Narnia are best left unstated), I only know The Wind in the Willows by reputation and the Disney short. I may need to pick it up to read to my son.

At this point, I am only scratching the surface. I may (or may not) have hit all of the areas. Scanning through my screenshots, I took one or more snaps in each of the 6 disks, so I at least hit them all. Dipping in a few more times over the next few days, I discover that the Dragon’s Tower was nothing more than the rook on a giant chessboard, and that we can find a spaceship hidden in the mountains. My favorite discovery is that we can find the lamp post from Narnia right near the beanstalk, if we open and enter the wardrobe we discover in the book.

There might be more, but I’d like to leave it this way. I am glad to leave it with the feeling that there are other undiscovered corners.

Time Played: Approximately 2 hours (including all versions)

|

Well, a few colors anyway. |

Now in Color!!

I have less to say about the DOS re-release of The Manhole than you might expect. Released only a year later, the team at Activision (aka Mediagenic) had the difficult task of porting a HyperCard application-- perhaps the most “Macintosh” development environment possible-- onto DOS. Doing the port took more engineers and development time than the original game, a significant investment that at least demonstrated that Activision was serious about the success of this children’s game.

Despite the solid effort, I’m not sure it really works. The color graphics never sing to me, although the background music and animation work considerably better than my double-emulated PPC version. There was something inherently charming about the storybook style of the original that is lost in color. Or, at least, lost in the limited color translation that they were able to do.

|

The whiteness that suggested a blank page in a storybook is now orange. |

|

The castle, at least, is suitably spooky. |

|

Not quite the impact of the original. |

I do not know the impact of the DOS version, but it also wasn’t the end of the story. The Manhole has been re-released several times since. Due to the expanded content and long delay in release, I am inclined to think of the “Masterpiece Edition” as a new game entirely. We could consider covering it when we get to 1995.

|

| The 1995 edition was a mix of the 3D pre-rendered art developed for Myst and traditional line drawings. It warrants further investigation in the future. |

Final Rating

How can I rate a piece of my childhood? Carefully! Truth be told, this isn’t an adventure game as we know them and it’s difficult for our rating to make sense against what this game is trying to accomplish. I’ll do my best to put it in perspective and try not to be overly biased.

Puzzles and Solvability - For a game with nearly no traditional puzzles, we might be tempted to just drop a zero here and move on. But “nearly no puzzles'' is not the same as “no puzzles” and we are constantly rewarded and teased with things that we can explore and click on to take us to new places within the game’s fantasy realm. The pool of water might be the only real puzzle (and a simple one at that), but the true puzzle of this game is finding everything there is to find; even now, I want to dive back in and see if there is something else I could tinker with. My score: 2.

Interface and Inventory - It’s impossible to stress how simple this interface is. All interaction is clicking and we get hints of what the game might do based on changes in the mouse cursor. (It changes to an arrow for movement, a finger for exploration, etc.) Compared to the UI clutter of most games of the era, it’s a breath of fresh air. Maybe this was all they could build within the limits of HyperCard, it’s a masterful application of those constraints. My score: 5.

|

Clicking through the boat labyrinth with a finger cursor. |

Story and Setting - This category is challenging because there is little “story” here, but plenty of “setting”. What story we have is what we make of it: a child exploring a fantasy world and discovering its denizens. There’s no goal or overarching plot. The setting is beautifully connected impossibilities, a child’s imagination run wild, and a constant exploration on the meaning of scale. My score: 4.

Sound and Graphics - For the purposes of this review, we consider the original release, the Mac CD-ROM version, and the DOS version together but we really don’t need to. The color graphics of the DOS version don’t hold a candle to the higher-resolution black-and-white graphics of the original. The background sounds and sound effects are perfect and while I was unable to hear the CD-ROM version’s score as originally intended, it is wonderful and so much more than anything we’ve heard by 1989. My score: 7.

|

The hidden Narnia lamp post. |

Environment and Atmosphere - This game is environment and atmosphere. Robyn Miller’s perfect stream of consciousness world, drawing me in to click on just one more thing to see what happens. Papers could be written on the complexity of the design, the way the game plays over and over again with scale, and so much more. This was a master class in atmosphere, as far as I am concerned. My score: 8.

Dialog and Acting - There is recorded speech! In 1989! That said, while the characters are well-drawn and have a few interactions each, there’s not all that much dialog here. This is a game that wants to present its story through images rather than text and so those few interactions aren’t quite enough to win us a high score here. My score: 3.

Let’s add up the points and see how badly I’ve upset everyone who claims that this isn’t an adventure game: (2+5+4+7+8+3)/.6 = 48 points!

That is a great score, but also one that I see as fair. The Manhole has some amazing elements, but it’s not an adventure game exactly even though it will lead to some very big adventures in our near future. It’s still in the top 30% of all games we’ve reviewed for the site (around the same level as The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Planetfall for games I have reviewed).

I hope you enjoyed our 100th Missed Classic. The Manhole was an important game in my development as a player of games and as a computer geek. I have at least one more side story to cover before I jump back into Infocom games. With luck and a bit of free time, you’ll get that in around 10 days. See you then!

Sources

For the history portions of this review, I am indebted to:

- The Digital Antiquarian’s coverage of both The Manhole and Myst.

- The Secret History of Mac Gaming by Richard Moss.

- Ars Technica and their Feb 21, 2020 interview with Rand Miller.

- Richard Moss’s 2018 interview with Robyn Miller to celebrate The Manhole’s 30th anniversary.

- Cafe Utne’s profile on Robyn and Rand Miller from 1995.

- Grantland’s 2013 look back on the 20th anniversary of Myst.

- The Computer History Museum’s profile on Rand Miller.

Growing up as as kid, I played both The Manhole Masterpiece Edition and Spelunx on our family's Macintosh. Though I remember the first of these as being titled "The Manhole II" for some reason, a title I can't find mention of anywhere on the Internet...

ReplyDeleteHappy Halloween! Timing didn't work out *exactly* right, but there will be a monster-themed Missed Classic coming out in 3 days. :)

ReplyDeleteWhy is the Elephant talking out of it's nose?

ReplyDeleteEr... he sounded a bit nasally to me...

DeleteGlad you focused on the Macintosh version. The 1-bit artstyle of games like this have aged better than most others of the era up til about EGA and Atari ST. Wonder if that's because people utilized the Macintosh better or if its because artists used Macintoshes instead of other computers.

ReplyDeleteI wonder if the animation speed issue is something you can fix? If you were on Mini vMac there's an option to change the speed somewhere, along with a help menu.

My impression is that the black and white Macs offset their lack of colors with a higher base resolution. I'm not positive in practice though and I do not know what resolutions were commonly supported in 1988. If you compare the DOS vs Mac screenshots above, you can see the impact the resolution difference had in practice.

DeleteI tried to get the Mac speed correct, but couldn't manage before I needed to write. I was using Basilisk II for 68k Mac emulation, but switched to SheepShaver instead for PPC Macs. For whatever reason, screen draws on Manhole with Basilisk were insanely slow, even when emulating a 68040. SheepShaver gave a much better presentation overall, except now the speed was too fast. I have not tried vMac.

Macintosh did offset their lack of colors with a higher resolution, though DOS could in theory work like a Macintosh. There's an unused by most games high resolution B&W mode for CGA. The only game I can think of that uses it was Rise of the Dragon.

DeleteSheepShaver seems like overkill for a '88 Mac title, but I admit I've never played this particular title. vMac worked fine for me for everything I've played on it, but I've played more action-based titles. Hypercard could do some kind of tricks that don't work well in some emulators though. Either way, Macintosh emulation is insane to get working, especially once we get into the '90s.